“You know, people really remember it vividly. It feels like it traumatized people and that’s just fine. That’s called catharsis…”

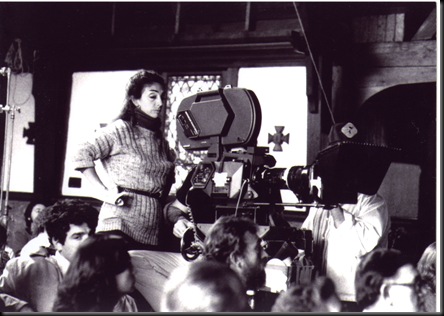

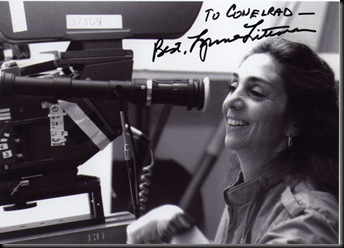

Director Lynne Littman on her film Testament

Since its release on November 4, 1983 (a few weeks before the network broadcast of The Day After) Testament has remained a haunting cinematic artifact from the last years of the Cold War. President Ronald Reagan’s first term arms buildup and his administration’s endorsement of civil defense had heightened fears of a nuclear war with the Soviet Union. It was in this tense atmosphere that a new wave of nuclear films was produced. The Day After, a heavily promoted and controversial “event” TV movie, was undoubtedly the best known of this crop.

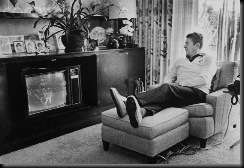

As has been reported in several biographies, The Day After had a profound impact on the president. Indeed, Reagan wrote in his diary on October 10, 1983 that the movie had left him “greatly depressed.” It has been suggested by historians that this movie played a part in changing the commander in chief’s mind about the arms race. Four years after watching it, Reagan infuriated conservative hawks by signing the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty with the USSR. It is unknown whether the president ever saw Testament, but it is highly unlikely that he did—because if The Day After “depressed” him, Testament would have put him in the hospital.

To this day, Testament retains the power to induce an almost crippling sadness on the part of the viewer. The same cannot be said of its massively hyped genre cousin.

A few years back, CONELRAD wanted to explore the creative evolution that led to this amazing film. Director Lynne Littman was kind enough to indulge our request for an interview. Remarkably, Testament was Ms. Littman’s first dramatic feature film. She had previously worked in the field of documentary, winning an Oscar for her short film Number Our Days (1976). Ms. Littman was open to all of the questions that we posed to her and pulled no punches. We hope that this interview will serve as an informative companion to the film, a kind of textual director’s commentary (the DVD, unfortunately, lacks a commentary track, but is otherwise excellent).

CONELRAD: What inspired you to seek the rights to Carol Amen’s short story The Last Testament?

LITTMAN: I was looking for a film to do and it was in Ms. Magazine, and at the bottom of the story, it said Ms. Amen lived in Sunnyvale [California] so I called Information in Sunnyvale. It was easy to find her and she was gracious and she sent me to her agent. And the rest was kind of funny, because when I went to American Playhouse to get money for the film, Lindsay Law [who was the head of American Playhouse] said “I’ve got this story from half a dozen people, why are you any different?” And I said, “Well, I have a cancelled check for the rights.” I had spent one of the most unpleasant years of my life being an executive at a television network, and what I did learn was to get the rights.

CONELRAD: You paid a thousand dollars?

LITTMAN: I paid fifteen-hundred. That was the option. I don’t remember how much we wound up paying her, but it was against a fee.

CONELRAD: What was Carol Amen [1933-1987] like? Did you keep in touch with her?

LITTMAN: I did. We certainly invited her to the set whenever she wanted to come. She did come, she came with her family. She was very lovely, very simple. I think she wrote religious pamphlets for airports. So when she said that she awakened in the middle of the night and this story came to her in a vision, she literally meant it. I mean I thought she was joking when I first heard it, but then I realized she was telling me the truth. And she sat down and wrote all night and finished the story. It was a very, very complete story. I mean each portion of it had a beginning, middle and end and each portion of it allowed for expansion, so it was quite a wonderful story. It just takes your breath away.

CONELRAD: How did you engage the services of John Sacret Young to do the masterful adaptation of Amen’s story?

LITTMAN: Yes, he wrote a script that was as good as her story. He was recommended to me by several friends and I went and met him and he basically threw me out of his office because he had asked me what I had read of his and I said “nothing,” and he said, “Come back when you know who I am”—which I immediately loved him for. So I went home and read everything he’d written. And actually, I was interested in him mostly because of a novel he wrote called The Weather Tomorrow. And I liked the way he wrote about women. So I didn’t hire him because of any of his television screenplays. He’s just a wonderful writer. [Editor’s note: Young went on to co-create the ABC drama China Beach and write for and produce NBC’s The West Wing.]

CONELRAD: How much involvement did you have in structuring his script?

LITTMAN: Total. It wasn’t collaborative—he writes alone which is terrific. But [anthropologist, writer, filmmaker] Barbara Myerhoff [1935-1985] and I went through—because I loved her mind—the [original] story, beat-by-beat and decided what values I wanted to have happen in each scene. And I think I gave ten pages of notes to John and sent him away and he did it.

CONELRAD: How many drafts were there? Were there drafts and then edit notes and then more drafts?

LITTMAN: Yeah, I mean…but not many. He pretty much had it. There were changes. He writes so seductively that you actually have to force yourself to see if there’s a scene there—or if he’s just writing, and, you know, there’s nothing to shoot. I don’t think we had any wild disagreements about anything. As I recall, none at all.

CONELRAD: Was John Sacret Young as enthralled by the original story as you were?

LITTMAN: Oh, yeah. I mean, it certainly wasn’t the money.

CONELRAD: How was the cast assembled? Did you choose Jane Alexander because you knew her from your days at Sarah Lawrence College?

LITTMAN: Yeah, I mean I didn’t know anybody. I had never been anywhere near a dramatic project. That’s not true—I had done one short dramatic film that was so bad I took it out of [circulation]. It was just disgraceful. I can’t look at it to this day. It was for a non-profit agency and it was shocking. The leap [of improvement] between that and Testament is almost fictional. So, yes, I had gone to school with Jane and I didn’t know her well—she was two years ahead of me. But I knew her well enough and she had read the story. And she was far more involved in the…She was involved with [anti-nuclear activist] Helen Caldicott, whom I didn’t know about. I didn’t know anything about this subject. It was not my issue.

CONELRAD: So you were attracted to the story on a humanistic level?

LITTMAN: Totally. I mean, on an emotional level. I was not part of any anti-nuclear movement at all. Nor was I afterwards. You know, afterwards, I felt like I gave at the office.

CONELRAD: How did you get William Devane?

LITTMAN: Through an agent. I mean he was perfect. He was impossible.

CONELRAD: What do you mean?

LITTMAN: He told me he could ride a bike. He told me he could really ride a bike. And the definition of the character was that he was a real bike nut—a real competitive, semi-professional bike rider. So we went out and spent the first outrageous portion of our budget and got one of these Italian jewels, you know, that’s so skinny you could practically balance it on your finger. And he took a look at it and nearly died. And the first thing he did was take off the stirrups. Well, anybody who takes off the stirrups doesn’t know how to ride a bike. I mean and I know that because I don’t know how to ride a bike. And that was the first day of shooting, because we were going to knock it off—the simple stuff, no acting, just bike riding. And he was arrogant and we had a real break down. And I finally went up and he was sitting up in the house and I said “Listen, you know more about how to do this than I do. You’ve been on a thousand sets, you’ve worked with fantastic directors, but I know this script and I know this better than you ever will and you said you would come to work for me.” And he apologized and he did his job and then after the fact he apologized profusely. He was wonderful. He had a tiny part and he was wonderful.

CONELRAD: In a New York Times interview preceding Testament’s release you mentioned you had spoken to one of the Hiroshima Maidens…

LITTMAN: Yes, I think she was. I don’t know how many there were, but I think she was. She was working with burned children at Cedars-Sinai [hospital] and she devoted her life to that. And I thought at one point that I would have another element of the film—I would have the story interrupted by these witnesses.

CONELRAD: Like in Reds (1981)?

LITTMAN: Yeah, it may have been influenced by that in thinking that I would break the drama and go to real people. And then didn’t. It was an aesthetic question, it wasn’t political, it was really whether I was going to use that as another color.

CONELRAD: What other interviews did you conduct to prepare for the reality of the film?

LITTMAN: I didn’t. Because it doesn’t have reality.

CONELRAD: You had mentioned that you…

LITTMAN: Called civil defense. I called civil defense. Yes, I called up the local civil defense office in L.A. and [explained we’re] making this film and what would they suggest the best action that citizens could take [in the event of a nuclear explosion]. And they said, “Use some plywood on your windows.” I mean we couldn’t believe it. Couldn’t believe it! After that answer there was no more research to be done. I mean, what’s to say?

CONELRAD: One of the things we like about Testament is that the explosion comes out of nowhere…

LITTMAN: Comes out of the TV.

CONELRAD: …And the people come out of their houses like they would after a tornado, congregating outside their houses even though we’ve been indoctrinated about the dangers of fallout and to go to the basement. But in reality people would go outside…

LITTMAN: Of course you would—you’d run outside to find your neighbor.

CONELRAD: Right, because human nature trumps all that indoctrination…

LITTMAN: Yeah, the thing that I thought was authentic about this was the human behavior. That’s why there was no research. The only research we did, actually, was in the script. In the script, you know, there’s the doctor and the other people testifying [in the town meeting scenes held in the church] which is the weakest part of the story. We had to get some of it [facts about the effects of radiation] in and then when you see her lose her hair…[the audience understands what is happening]. We did research an answering machine. John and I both suddenly got crazed about finding an answering machine where you pull the plug out and it activates on batteries. [Editor’s note: A scene late in the film involving the answering machine is critical to tying up a loose end in the film].

CONELRAD: What was the child actors’ view of the story of Testament? How did you guide them through the grim subject matter?

LITTMAN: It was only Lukas [Haas] who was an extraordinary boy. I think he was six. And he had never worked before and my casting director found him in a Montessori school. He was unbelievably precocious and I took him aside and I said, “You know, Lukas, your [character’s] father…” And he said, “Yeah, he got zapped in a phone booth in San Francisco…” And I said, “You got it.” And I found that with my own kids, they have a very strong sense of real and movie.

CONELRAD: Was the character of the little Asian boy with Down syndrome named Hiroshi [played by Gerry Murillo] supposed to be a symbol of the victims of Hiroshima?

LITTMAN: Not his condition. I mean that was certainly not intentional. Not that connection at all. He was an innocent, vulnerable.

CONELRAD: But was your intent to have a Hiroshima connection to the character?

LITTMAN: Well, sure, if you’re going to name him Hiroshi, you’re going to make the connection, but it wasn’t a big deal.

CONELRAD: But was that a calculated choice on your part because that’s how a lot of people took it.

LITTMAN: Well, I guess it is, but it wasn’t larger than what it is. I mean, yes, we [the United States] did Hiroshima, yes, we damaged people. Sure. How can it not be. And it may have been heavy-handed. Maybe we should have called him Yoshi and probably I would have, now.

CONELRAD: Was filming the story a generally depressing endeavor?

LITTMAN: It was odd. It was not only not depressing, it was like people were levitating. I mean, I had no idea. This was my first [dramatic] film. I had no idea that crews don’t drive forty-five minutes every night to come to the dailies. I mean the entire crew came every night to watch the dailies. I didn’t know that’s not what you did. I didn’t know that you usually didn’t let the crew watch the dailies. I didn’t know any of that stuff. They wanted to come, great, the room was big enough.

CONELRAD: So, the atmosphere on the set was a generally happy one?

LITTMAN: It was not only happy…This is all in retrospect. I had no frame of reference. It was truly amazing.

CONELRAD: That would surprise most people because it is such a depressing movie…

LITTMAN: But making movies has nothing to do with a finished movie. It’s totally fragmented, you’re worried about other things like whether Leon Ames [Henry Abhart, the HAM radio operator] is going to get through a scene. I mean I was hanging on a roof with cue cards because he was having a bad day. And he was an absolutely wonderful old gentleman and what you’re worried about is whether he’s going to be insulted and is he going to say his lines. So, the last thing you’re worrying about is a nuclear holocaust.

CONELRAD: Were you aware that Sierra Madre [where Testament was filmed] was the same location Don Siegel filmed Invasion of the Body Snatchers?

LITTMAN: No, I had no idea. We found this adorable little town. I had no idea. It was a pretty wide open space. Now they have a film commission. Now they’re all organized.

CONELRAD: Do you recall the start date and the end date of the 28 days of shooting?

[Editor’s note: At this point Littman moves over to a bookcase with her diaries and locates her book for 1983.]

LITTMAN [Quoting from book]: Start shooting Sierra Madre, Thursday, January 13th. End shoot in Sierra Madre on Valentine’s Day—Monday, February 14th. I play bag lady.

CONELRAD: You’re in the film?

LITTMAN: Yep. [Quoting again] Wrap party, February 19th.

CONELRAD: What was the wrap party like?

LITTMAN: I got so drunk, my husband had to carry me home. I was completely gone.

CONELRAD: How long were the shooting days?

LITTMAN: They weren’t outrageous. We were very good. I was very organized.

CONELRAD: Were the townspeople helpful? Did you utilize the townspeople?

LITTMAN: You know, I didn’t deal with them a lot. I had a very good…I had a Marine as a UPM [Unite Production Manager]. It’s quite possible that he made things work as smoothly as it did. There was one [resident] who didn’t do his awning.

CONELRAD: To conform with the post-attack look of the film?

LITTMAN: Whatever it was, he wouldn’t let us dirty up the front of his store. But [in general] they were very good. I only heard about it from a distance. I was treated like a real director and I behaved like one, I guess.

CONELRAD: What was the biggest challenge in filming?

LITTMAN: Staying on my feet.

CONELRAD: Was it draining?

LITTMAN: It’s a total loss of privacy. And I would go to the toilet to hide because the better the crew is, the more questions they have. The more you respect them, the more you want to give them the correct answers. They’re going to go off and work based on what you say. It’s wonderful, it’s thrilling.

CONELRAD: Some reviewers criticized “Testament” for not depicting the visible ravages of radiation sickness. How do you respond to that?

LITTMAN: I don’t care about that. They were wrong. I mean, that’s another movie. You know, The Day After basically killed us.

CONELRAD: We’ll return to the subject of The Day After. Did it strike you as odd that Testament—in addition to the more traditional award nominations (including an Oscar nomination for Jane Alexander)--was nominated for awards by science fiction foundations such as the French Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival [Editor’s note: Testament also won a Christopher Award; Jane Alexander was nominated for a Golden Globe and an Academy Award for Best Actress, but lost both times to Shirley MacLaine who won for Terms of Endearment.]?

LITTMAN: It is science fiction. No, if I could have gone to Avoriaz, I would have. It is science fiction.

CONELRAD: But it’s a very tangible kind of…

LITTMAN: Well, it’s just political. What it is that’s different from most science fiction is that it’s emotional. That’s the only thing that makes it strange for science fiction. Most science fiction is completely....even Rod Serling, whom I adore, is not emotional.

CONELRAD: So you embrace the notion that your film is science fiction?

LITTMAN: Well, it certainly ain’t fact. It ain’t science fact. You mean I should be insulted?

CONELRAD: No, it’s just most people don’t think about Testament as science fiction.

LITTMAN: Well, I don’t think they do and I certainly don’t, but I’m not angry at the science fiction people. They’re pretty brilliant. If I think of them as a country, I can’t see it [Testament] fitting in. You know, I can’t see a bunch of science fiction freaks blubbering and they’d have to. It’s just not something you think of when you think of science fiction. But if they want to embrace it, fine by me.

CONELRAD: Do you recall your reaction to Variety classifying Testament as a “suspenser” in its 10/19/83 review?

LITTMAN: No, I don’t remember that at all.

CONELRAD: Does that label amuse you?

LITTMAN: Well, that was what the amusing thing was that people actually were in suspense. People would come up to me afterwards and say, “Did William Devane come back?” I would say to them, “Not a chance! Are you out of your mind?! No! They’re all going to die. This is what is happening here.”

CONELRAD: It was funny to see these industry publications try to pigeonhole the film.

LITTMAN: Well, what would they call it? You could call it a horror film, too. You could probably put it in just about every category except romance. It’s a family drama. It’s not a musical either, but James [Horner] did the best score he’s ever done.

CONELRAD: Were you surprised that conservative columnist Ben Stein wrote approvingly of Testament? In his columnm by the way, he asserts—wrongly—that the Russians were the instigators.

LITTMAN: I think his wife worked at Paramount which wound up distributing it, so I don’t know at which point… [Laughs]

CONELRAD: So, you think it may have been… [suggested that Stein write about the film].

LITTMAN: No, I’m sure not. I don’t mean that. But she did work at Paramount. No, the funny thing about this movie is that—just as it’s multi-genre—it’s totally apolitical, so anybody can adopt it.

CONELRAD: On the other side of the political spectrum, were you surprised that Ms. Magazine–one of the two periodicals that originally published Carol Amen’s story—took rather dismissive potshots at the film version? [Editor’s note: Carol Sternhell, missing the point, wrote in the January 1984 issue of Ms. that the children in “Littman’s sentimental film could have been dying of anything, an outbreak of plague, a bad case of the flu…” Sternhell also took issue with the “schmaltzy music” and “heavy-handed symbolism.”].

LITTMAN: They said nothing. I didn’t even know that they had seen it.

CONELRAD: We have the review…

LITTMAN: Really? I was so pissed at them because I had credited them. I mean I didn’t know they had written anything—I wouldn’t be pissed at a bad review. But the fact that they didn’t do a major story about me and about the film which I gave them every credit for…It was unbelievable to me. In every interview I was thrilled and I said Ms. Magazine…

CONELRAD: Even though it was originally published in a…

LITTMAN: A Catholic literary magazine [Editor’s note: Carol Amen’s original story, The Last Testament, was published in the September 1980 issue of Saint Anthony Messenger]. And you know she had to change the ending? Did I tell you that?

CONELRAD: No, please tell us about that.

LITTMAN: She had written the story originally where the mother commits suicide and they wouldn’t publish the story because it’s anti-Catholic.

CONELRAD: We’re going to come back to that because we’d like to ask you about how you chose to end the film…

LITTMAN: Anyway, screw Ms. Magazine.

CONELRAD: How did you react to some critics dismissing the film as a feminist “weepie”? Were you aware of the criticism?

LITTMAN: You know, I was in such euphoria. It was so wildly successful for me beyond my belief that at that point I didn’t care what anybody said. I mean, who cared? Paramount sent me to Europe on the most unbelievable tour—I will never stay in places like that again.

CONELRAD: So you’re not one to fixate on reviews?

LITTMAN: Well, the major ones were pretty terrific. I mean Sheila Benson’s review got me [distribution at] Paramount. And the [public] response was overwhelmingly wonderful.

CONELRAD: The early Reagan era saw a revival in the production of films about nuclear war. What did you think of The Day After and Threads, the two films that Testament is most frequently compared to?

LITTMAN: The film that I saw that scared the…I mean I think I left the theater and threw up, was Peter Watkins’s The War Game [1965]. It may have been the first film made [in the genre of] false documentary.

CONELRAD: How did you see it?

LITTMAN: I saw it in London in a theater in Piccadilly Circus around 1964 or ’65 and I was sick and I never forgot it—ever. And, so, to the extent that I had a model, that was my model. I mean, The Day After came out simultaneously, so I never saw it until later. And I don’t know if I ever saw Threads.

CONELRAD: How did the publicity of The Day After impact you?

LITTMAN: They did so much publicity, it was like a tsunami and they drowned me. They simply drowned me. After that, it wasn’t a matter of whether you had seen the movie. After that amount of publicity nobody wanted to go near the theater. And that made me sad because I think mine was a much better movie.

CONELRAD: What is your favorite Cold War film?

LITTMAN: The War Game. It was a stunning movie. You know, I’d have to see it now. It was as frightening as I think Testament is because it was physical. I don’t remember how they did it. All I remember is a kitchen where furniture flew around the room. In a way it was domestic, because the scenes were familiar. I don’t remember the people, but I remember the physical destruction and the images and the black and whiteness of it.

CONELRAD: There are many descriptions of the emotional reaction your film elicited from viewers back in 1983. Do you recall how it felt to have been responsible for such a film? Do you recall being in a theater…

LITTMAN: The night of the big screening—I paid for the screening—at the Writers Guild—I had invited everyone who had been to my wedding. I mean it wasn’t an industry screening, it was my life. The editor and I were sort of pacing at the back of the room, the auditorium. We went in and out, but we didn’t really watch. And we listened and we heard a plastic wine cup—it was dead quiet. And we heard this plastic wine cup rolling down the aisle and we thought, “Oh, God.” And then, at the end, nobody moved and we were heartbroken because we thought [the audience did not like it or get it]. And then they staggered out. Then it went to Sundance. Not to Sundance, to Telluride [Film Festival].

CONELRAD: Didn’t it play at Sundance?

LITTMAN: Well, there was no Sundance [as we know it today]. They had a wood hut and a projector. And it was in the summer and Lindsay [Law] and I went up for there, I think, for three days with the film under our arm and we showed it.

CONELRAD: We talked to Linda Remy who co-wrote the story for Desert Bloom (1986) and she remembered seeing a screening when she was there in 1983.

LITTMAN: Maybe she was and it was shown in a tiny room. I remember Armand Assante was there with his brand new baby and he and his wife and his baby were about to go in [to the screening] and I said to him, “Don’t go in there,” and they didn’t. That would have been just ridiculous. But I mean, Sundance—it was a wooden shack.

CONELRAD: A little different from today.

LITTMAN: No question.

CONELRAD: Did people come to you after the movie at the Writer’s Guild and Sundance?

LITTMAN: Well, yeah, but the big response, the big shock response was Telluride.

CONELRAD: What was going through your mind when you saw that kind of reaction?

LITTMAN: I was thrilled.

CONELRAD: Because you knew you had a film that worked?

LITTMAN: I don’t even know that I knew then. I guess I did. They showed it in the afternoon because nobody thought it was any big deal. The film that was supposed to be the big film of that season was El Norte which was a very lovely film, so they put mine on in the afternoon…

CONELRAD: Not realizing…

LITTMAN: Not realizing anything and then it blew that whole year away. People ran out of the theater to phone booths—this was before anyone had cell phones—to call and make sure their kids were still there. It was really funny. It was amazing. It was wonderful. I mean to feel that way about something that has value. And I learned that there’s a real fifty-fifty chance—and I think this is the way it broke down—that people would think it’s sentimental claptrap and just laugh at it. I was surprised that there was less of that than I’d expected. I did get a very interesting comment. Very early on I had wanted Julie Christie to be in it and I sent the story to her and she wrote me back this wonderful letter. I just met her recently. I had met her once then, but I just met her again. And she had written me this really thoughtful long letter about the fact that the naiveté [of the story] made it uniquely American, that Europe had been invaded and pulverized and was not as innocent. And I really learned then what turned out to be one of my most difficult lessons which is that for somebody who thinks of herself as very sophisticated, I make very American movies. And I make movies that have almost no interest anywhere else because they’re about America.

CONELRAD: So she was basically turning down your request to be in the film?

LITTMAN: It was very sweet. It was simply saying that, in a way, it was not relevant to her. And she was right. She’s very smart.

CONELRAD: So was Julie Christie your first choice to play the role of the mother?

LITTMAN: No, it was way before I think I even spoke to Jane [Alexander]. And there was also a period where Jane got another job and for a while it looked like she wasn’t going to be able to do this. Susan Sarandon came in, a lot of wonderful actresses who were not at all stars.

CONELRAD: In a preface to his Feb. 2001 article on “atomic” film/culture, Vanity Fair’s Bruce Handy confessed that he could not bear to watch Testament again even though he purposely watched every other “end-of-the-world” film to prepare for the article. He wrote of Testament: “It’s seriously the most disturbing film I’ve ever seen in my whole life—beyond traumatic.” Do you find that the common reaction to “Testament” is similar to Handy’s?

LITTMAN: You’re kidding? I don’t know whether to take it as an insult or a compliment. It should be the most depressing film. I would have been happy had he said the most threatening. So I don’t know how he really feels. He may have hated it.

CONELRAD: It is a traumatic film and that is the context of his statement. We didn’t get the impression that he hated it.

LITTMAN: I see. I’m now meeting people who say to me, “I watched that film with my mother—that’s my mother’s favorite film.” When people come up to me about the film, they get different. It’s like they’ve had some private experience with me. And they inevitably talk the baby in the bathwater [scene where Lukas Haas is hemorrhaging from radiation sickness].

CONELRAD: Does it surprise you that your film still provokes these reactions twenty years later?

LITTMAN: It’s wonderful. It does. You know, people really remember it vividly. It feels like it traumatized people and that’s just fine. That’s called catharsis to some extent.

CONELRAD: It seems that the overall lesson of the film is that life is precious and that the “mission” of the film is to avert nuclear war.

LITTMAN: Yes, that was the entire purpose. I mean this was not a real complicated goal. The funny thing is that, it seems to me, that all of my films have turned out to be about that, or most of them. They are about life on the edge of death which makes life precious.

CONELRAD: Did you want to end Testament on a hopeful note around the table with the candles and the “wish”?

LITTMAN: You know, I don’t like the last scene and I look at it now and it makes me uncomfortable because it breaks the dramatic convention—who is she talking to? You know, in the course of the film she suddenly becomes an uber voice and that’s wrong. And I wouldn’t do it now.

CONELRAD: You mean when she’s ostensibly talking to the kids?

LITTMAN: Well, she’s talking to the kids, but she’s saying, “To save the children…,” you know. It’s a violation of dramatic form. It’s wrong. I could have done it in voice over and that would have made it acceptable. It may still have been too preachy or too on the nose. I don’t know if anything had to be said. That whole scene could have been done silent and he [Ross Harris as Brad Weatherly] didn’t have to say, “What are we celebrating, mom?” [Editor’s note: Harris says “What should we wish for?”]. We’re celebrating life—it’s evident. You know, what you learn is that you need half of what you thought you needed if you’ve got the goods.

CONELRAD: Because you knew about Carol Amen’s original ending to her story, did it ever occur to you to…

LITTMAN: To have them die?

CONELRAD: Yes.

LITTMAN: I actually love when a movie continues after it’s over and by keeping them alive, the movie continues after it’s over. You walk out wondering if they’re going to die. And you have the fight with yourself—you know they’re going to die and you hope they won’t die, so that’s more powerful. You know, you start off a movie and you kill everybody. I mean that [allowing the remaining characters to commit suicide] would have made it silly. Maybe not, maybe if a European director had done it… but then it would have been European [Laughs].

Interview conducted by Bill Geerhart on January 28, 2003. CONELRAD would like to thank Ms. Littman for her hospitality and her willingness to speak at length about Testament. We regret that it took us this long to post this interview and we hope Ms. Littman will forgive us.

CONELRAD will be posting an extensive article on Testament in the coming weeks. Stay tuned.

1 comment:

Hi there mates, how is all, and what you would like to say concerning this

article, in my view its truly awesome in favor of me.

Click here to chceck my blog :: 오피사이트

Post a Comment